So hello good people of the internet, welcome to another OTHER VOICES, the series in which I shut up for a while and let my favourite people talk for a while. This piece comes from the ever great Corvid Longcoat, who introduces us to some very cool Voodoo/ Servants correspondences…

In an earlier post, I noted in passing that the Forty Servants work well with, and have some clear correspondences with, “New Orleans Voodoo.” These connections are worth exploring—and we’ll do so in this post—at least in order to make clear some of the links between systems based on archetypes, but also because magic seems to be inherently syncretic. We borrow, steal, and imitate from all over the map, and while it won’t do to pretend to practice a system we have little connection with, we can compare, contrast, and innovate.

As is my custom, a couple of distinctions will make the rest of my work easier. First, let’s distinguish between “folk” systems and “formal” systems. Without wishing to harden these categories, we can clearly see across a number of spiritual systems that elite practitioners guard access to their systems, and evaluate who can and cannot teach or practice. Across the same systems, people will appropriate elite practices, texts and frameworks, and adapt them to their own uses. The phenomenon of “folk saints” in Catholicism shows this quite clearly: these are saints, either apocryphal or folk hero[in]es elevated and venerated by the common people, rather than sanctified by the Church.

The next distinction will be between the various rubrics of voodoo. People spell it Vodou, Vodun, Voodoo, etc. Various related forms of Afro-Caribbean magic and religion—the so-called “African Traditional Religions”—include Candomblé, Santéria, Quimbanda, Lucumi, etc. Far from a fruitless attempt to define and distinguish these amazing systems, I will simply say that the version which we’ll be discussing is often known as New Orleans Voodoo. It is noted for its polyglot syncretism [something which may permeate the other systems as well], and its lack of formal hierarchy, making it a folk practice par excellence. No less an authority than Hoodoo teacher Cat Yronwode of Lucky Mojo insists that New Orleans Voodoo does not exist, except as a tourist attraction, and proceeds in one of her posts to list nearly every writer on it as a charlatan. From where I sit, that basically confirms New Orleans Voodoo as a living, non-hierarchical tradition, in much the same way as Catholic denunciation of Santa Muerte, for example, almost proves the efficacy of her veneration. Rather than use its geographical designator, I prefer to call it “folk voodoo.”

In any case, the correspondences we’ll look at are between a few of the Forty Servants and some popularly venerated figures in folk voodoo as a way of enriching practice, cultural exploration, and archetypal identification. There are 12 key ones I’d like to point out here, and probably many others awaiting deeper reflection and research.

Additional caveats: these are impressionistic connections, occasionally based on Tommie’s striking artwork. The artwork was never intended to be definitive, as I understand it, and certainly not canonical. We all have our own experiences and visualisations with the Servants, and of course voodoo loa and venerated personages have an enormous variety of appearances. If this piece serves any function, it would be to stimulate discussion so that I might learn a bit more about both the Servants and a range of voodoo variants. African Traditional Religions [as they are called, despite them not being specifically African, traditional or perhaps even “religions”] are a varied, thorny, and contentious subject, and these are meant as suggested discussion topics.

Intentional Parallels

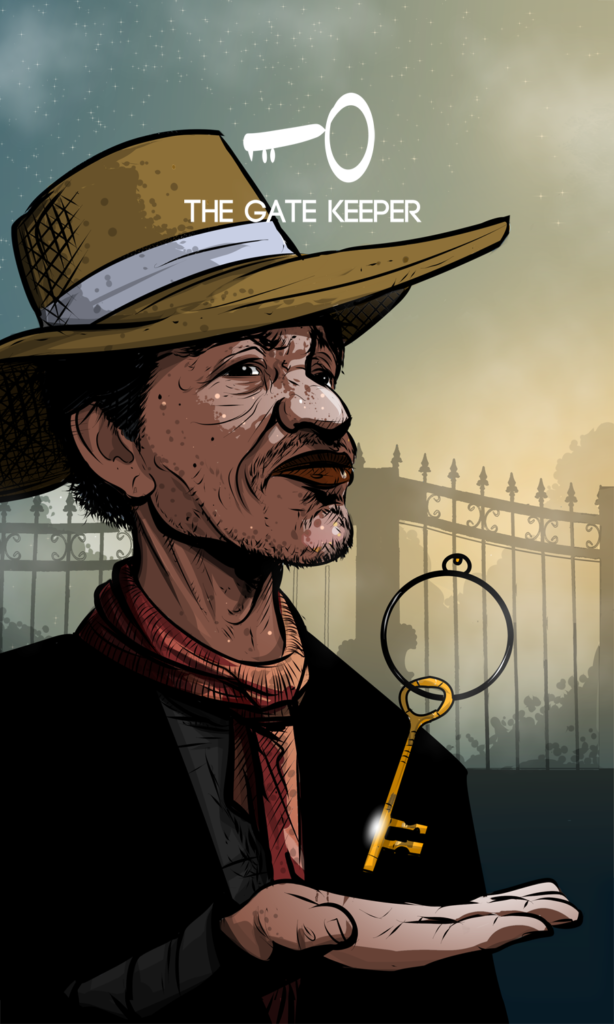

Without second-guessing Tommie, it’s clear that at least two of the Servants have intentional parallels with venerated voodoo personages/loa/orishas/deities: The Witch and The Gatekeeper.

The Witch – Forty Servants

The Witch and Marie Laveau. The striking, beautiful, and enchanting artwork for The Witch draws direct inspiration from the most famous portrait of Marie Laveau, the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans, and various touches—like the depiction of her likely grave in St Louis Cemetery #1 in NOLA and “XXX” often used by supplicants—indicate that this resonance was intentional. Laveau was a complex, powerful, and celebrated character in 19th C New Orleans, leveraging the contingent social power light-skinned women of colour had. She enhanced her reputation and power with ritual dances in Congo Square, and ceremonies involving snakes, various divination practices—her stool is on display on one of NOLA’s museums—and building a popular following. Martha Ward’s Voodoo Queen: The Spirited Lives of Marie Laveau is a useful counterpoint to Robert Tallant’s sensationalist biography also titled Voodoo Queen.

Laveau is venerated in folk voodoo, and offerings and requests are left at her putative grave. With good reason; her magical interventions are thought to be decisive.

The Witch, of course, adds a bit of magic to any situation, and for many of us working with the Servants, provides a loving, “bewitching”, and powerful patron who can do pretty much ANYTHING. Many Servants have defined scopes, but the Witch is about magic writ large, and my own experience is that she handles everything with grace and style, much like the spirit of Laveau.

The Gate Keeper – Forty Servants

The Gatekeeper and Papa Legba Let’s quickly get past the question of Legba/Ellegua/Exu. Whether these names are about the “same” cultural force or not is a thorny question, but there are striking overlaps and similarities. In New Orleans folk voodoo, he’s called Papa La-Bas [“over there” or “down there”]. Further, a huge range of cultural traditions have a spirit tasked with opening the spirit world to us, and often also carrying the Dead to their final resting places. These spirits often spend time at crossroads—think of Heimdallr, perhaps, where the Rainbow Bridge meets the sky—which explains their relevance in so many forms of magic.

The Gatekeeper’s artwork also recalls the “old Black man at the crossroads” famous from stories and songs of voodoo and Hoodoo. His sigil is a key, reminiscent of Papa La-Bas’ syncretisation with St Peter [another gatekeeper often depicted with keys]. Interestingly, HP Lovecraft’s Nyarlathotep is described as “Black”, and witch-hunting lore described a “Black Man” at a crossroads who guided witches to Sabbat. These connections are drawn out in Tomas Vincente’s book The Faceless God, exploring Lovecraft’s work as a source for magic.

But The Gatekeeper of the Servants has a similar function to Papa La-Bas: opening up trance spaces and “taking” people and objects to different places. Friends and I have used the Gatekeeper to find lost objects [another feature of Papa La-Bas] and to open up access to information from the past and future, as well as other physical locations in the present. The Gatekeeper and Papa La-Bas are both “master of roads and pathways”, whether those are literal, on the internet, or metaphorical or emotional.

Beyond the Intentional

The Healer and St Roch One of the most prevalent traditional functions for magic and “magico-religious” systems is healing. The Healer in the Servants—while of course no substitute for medical attention—has blessed numerous practitioners with relief from pains, emotional discomfort, and speeded up my own healing after surgery to a degree that astounded doctors.

St Roch—also known as St Rocco—is venerated as a healer in folk voodoo due to the historical St Roch [1295 or 1348–1379] working tirelessly with plague victims. His intercession is sought for healing, with obvious connections to the Servant’s own Healer. While there are chapels to St Roch in lots of places, due to the connection with French New Orleans, the chapel to St Roch on the rue St Honoré in Paris is enormously powerful. It also has a shrine to St Expedite, whom we will discuss in due course.

The Dead and Baron Samedi/Maman Brigitte The Dead gives us access to the literal dead, to the past, and to institutions and transition of all kinds. There is a clear connection with one of New Orleans’ most famous exports, Baron Samedi, the Master of the Graveyard. It’s probably useful to put his wife, Maman Brigitte, in connection as well, as the artwork for the Dead uses a female body. As one reveiwer noted the Dead’s sigil looks a bit like a top hat, one of the Baron’s signature marks. In any case, these two rule the graveyard, ancestors, and provide access—like the Dead Servant—to the powers of necromancy more generally.

The Fortunate and Assonquer The Forty Servants has a servitor of good fortune, The Fortunate. The Fortunate makes sure you are in the right place at the right time, and adds that crucial ingredient of good luck to any undertaking. This notion of synchronicity is picked up, in the work of at least one writer on folk voodoo, by a less well known loa called Assonquer. Kenaz Filan—whatever one thinks of his contemporary views—outlines Assonquer as a “forgotten” spirit of synchronicity and good luck in his The New Orleans Voodoo Handbook. My own explorations of the connections between The Fortunate and Assonquer indicate that—while there may be some adjustment in how the versions work with each other—they overlap quite a bit.

The Road Opener and St Expedite Artwork for the Road Opener recalls Ganesha, and Ganesha-specific mantras are also suggested in the Grimoire of the Forty Servants, but folk voodoo has its own version of the venerated figure who clears away obstacles: St Expedite. This may stem from nuns in New Orleans praying to the patron of their convent for deliverance during the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812. In any case, St Expedite is invoked for emergencies, quick solutions, and overcoming obstacles. Interestingly, he is often syncretised with Baron Samedi or [another aspect] Baron LaCroix, whom we have paired with the Dead. But the link with the Road Opener is virtually a no-brainer.

The Fixer and Joe Feraille The Fixer is literally a “wild card,” invoked when nothing else will sort the problem, and while not feared per se, the consequences of using him can be unpredictable. He is known to be a bit rough around the edges, and somewhat direct and occasionally harsh in his solutions. He corresponds to the figure of Joe Feraille [Iron Joe] in folk voodoo. Joe likes to drink, he likes to fight, and he is a wild card and a fixer. Joe Feraille is a version of Ogun, Ogun Fer, and it would take a long time to go into the various versions of Ogun, the Warrior Orisha. Joe is a New World variant, like many of the folk voodoo figures.

The Protector and Yon Sue The Protector Servant looks after us, and affixes to locations and things we want protected. A very portable ward. In New Orleans, Yon Sue or Monsieur Agassou is venerated as a protector. This protector spirit varies across African-derived New World traditions, but works quite well as the Protector.

The Carnal, the Mother, and the Erzulies The Erzulies, Erzulie Dantor and Erzulie Freda, have some overlapping qualities, but we will arbitrarily unpick them here with the help of some syncretisation. Erzulie Dantor is a powerful feminine archetype, and her portraits are often an African woman with a tribal facial scar. The scar led practitioners to syncretise her with Our Lady of Częstochowa, the Black Madonna, and so [despite her association in some quarters with sex] she connects strongly with The Mother. The Mother has a fierce love, and that fierce protection and love characterises the relationship of Erzulie Dantor with her initiates.

Erzulie Freda is often petitioned to help find a lover, and so she seems more connected to The Carnal. It bears emphasis that the Erzulies have widely overlapping feminine archetypes, and the separation of those archetypes into “mother” and “sexual” can be easily critiqued. While not necessarily something to view as fixed, if seen as alternate aspects of a deeper feminine deity/archetype, the potentially tiresome splitting of sexual and maternal aspects can be avoided.

The Father and Blanc Dani. The Father Servant has the quality of a restrained, paternal love. Wanting what’s best but not without boundaries, and occasionally dealing out some consequences as a lesson. In folk voodoo, this function might be handled by Blanc Dani, a version of the Archangel Michael. Blanc Dani is famously petitioned for help, and arrives giving lessons.

The Desperate and St Jude The Desperate is often used to “hand over” issues and anxiety when they feel too much. It feeds on these negative emotions, so handing them over both supports the Servant, and lightens our load. St Jude is famously the patron saint of lost causes, venerated and turned to when the cause is lost. While there are overtones of the Fixer, he seems more fiery and dangerous than St Jude, so the saint feels more connected to the Desperate.

In conclusion, it seems obvious that one could delve more deeply into something encyclopaedic like Denise Alvarado’s The Voodoo/Hoodoo Spellbook and develop associations—either with spirits brought from Africa, New World variants and developments like Baron Samedi, or Catholic Saints—for the Forty Servants. The point here is of course not to show what anything “really” is, but to allow practitioners a wide play of association, freedom and material to use in syncretic magical practice.

Happy Conjuring!

Corvid Longcoat is a Black Jewish Taoist part-Scottish martial artist practising in a number of occult and magical streams, including of course The Forty Servants. He lives in the US, and also studies the history and anthropology of the occult. He is not a witch.

LINKS & STUFF:

BLOG

– ADVENTURES IN WOO WOO

THE FORTY SERVANTS

– All Info on The Forty Servants here!

THE FOUR DEVILS

– INFO AND DOWNLOADS

– SIGNED ALTAR CARDS/ ART PRINTS

MEDIA

– Adventures in Woo Woo Podcasts

– Tommie Kelly Youtube

SOCIAL

– Adventures in Woo Woo Facebook

– The Forty Servants Facebook Group

– Twitter

– Discord

– Instagram

–